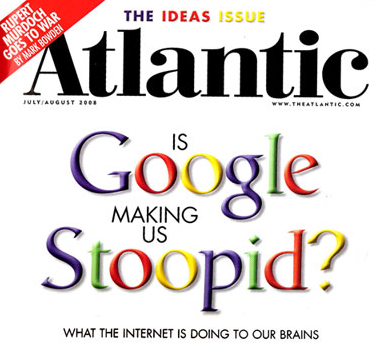

A Shallow Argument: Nicholas Carr and the Internet

Friday, July 2, 2010 at 8:14AM

Friday, July 2, 2010 at 8:14AM

Among its many errors of logic and argument, Nicholas Carr's book, The Shallows: What the Internet Is Doing to Our Brains suggests that the plasticity of the brain — its malleability, means that the generation now heavily involved with, and indebted to the Internet, is having its brains rewired. Aside from the obvious problems in talking about the brain as an electrical system, the supposed plasticity of the human brain is far from being proven although it is in an important area of research in the neurosciences. It is true that the brain is far more capable of adaptation than previously thought, and there is evidence to suggest that learning at all stages of life contributes to a "healthy" brain. However to draw the conclusion, as Carr does, that we are in the midst of a crisis which is redrawing the boundaries of how people think (and most importantly what they do with their thoughts) is alarmist and counter productive.

Carr's panic at what is happening to "us" — distracted multitaskers who no longer read or experience the world with any depth or rigour — perpetuates the century's old hysteria about the effects of new technologies on humans. Stephen Pinker, who actually does research in the neurosciences skewers the simplicity and reductiveness of people like Carr in a recent New York Times article. He says, "Critics of new media sometimes use science itself to press their case, citing research that shows how “experience can change the brain.” But cognitive neuroscientists roll their eyes at such talk. Yes, every time we learn a fact or skill, the wiring of the brain changes; it’s not as if the information is stored in the pancreas. But the existence of neural plasticity does not mean the brain is a blob of clay pounded into shape by experience."

Of even greater interest is Carr's transformation of Darwin's theories of evolution into claims about the speed with which the Internet is altering human biology. This fast forward approach to human evolution has its attractions. After all, humans were not around to witness millions of years of evolution, so it is easy to draw simplistic solutions to explain shifts in human activities and modes of thinking.

Carr's moral panic (taken up and reproduced by hundreds of journalists in newspapers and blogs seemingly desperate for some explanation as to why they are hooked to a medium they haven't thought about with enough depth and historical range) suggests that evolution is like Lego blocks. Once you put a few blocks into place, you have a structure, and once you have a structure, presto! you have evolved!

Carr's argument is just a variation on intelligent design. Replace god with the Internet and you have a power so great that humans are not only its victims, they are growing new brains to accommodate its vicissitudes.

Why do balkanized versions of genuinely interesting and important research projects into human adaptability get transformed into this type of discourse? It is probably not sufficient to suggest that every new technology generates panic among those who least understand either its present use or future transformation.

After all, had Carr taken even a minimum peak at the 19th century, he would have noticed that among other assertions, the telephone was described as a killer of conversation and human interaction (an attitude that lasted well into the 1960's). He would also have noticed that the cinema was described as a terrible distraction that among its many effects would probably lead to the death of literature and theatre. Photography was lambasted for its potential to lie and convince the gullible masses that the truth of an event could be found in images.

But, Carr is not the problem here; he is merely symptomatic of an ever growing and worrying trend to ahistoricism among so called public intellectuals. Those who should be the most sensitive to the nuances of change and the shifting relationships among individuals and their communities and the communications technologies they use are now sanctimoniously declaring that the public is being dumbed down. Carr, of course, never spent any time doing an empirical study because it would have taken him years to complete. He accuses internet dwellers of swimming in a sea of illusions without asking any hard questions about how he came to that conclusion.

His lack of attention to history is what he suggests internet users have devolved into, and, in so doing, he imposes on this vast and ever changing community with all of its diversity and multi-national character a superficiality of intent that he himself creates with his own very shallow arguments.