From Quantum of Solace to Sherlock Holmes

Saturday, January 2, 2010 at 9:59AM

Saturday, January 2, 2010 at 9:59AM

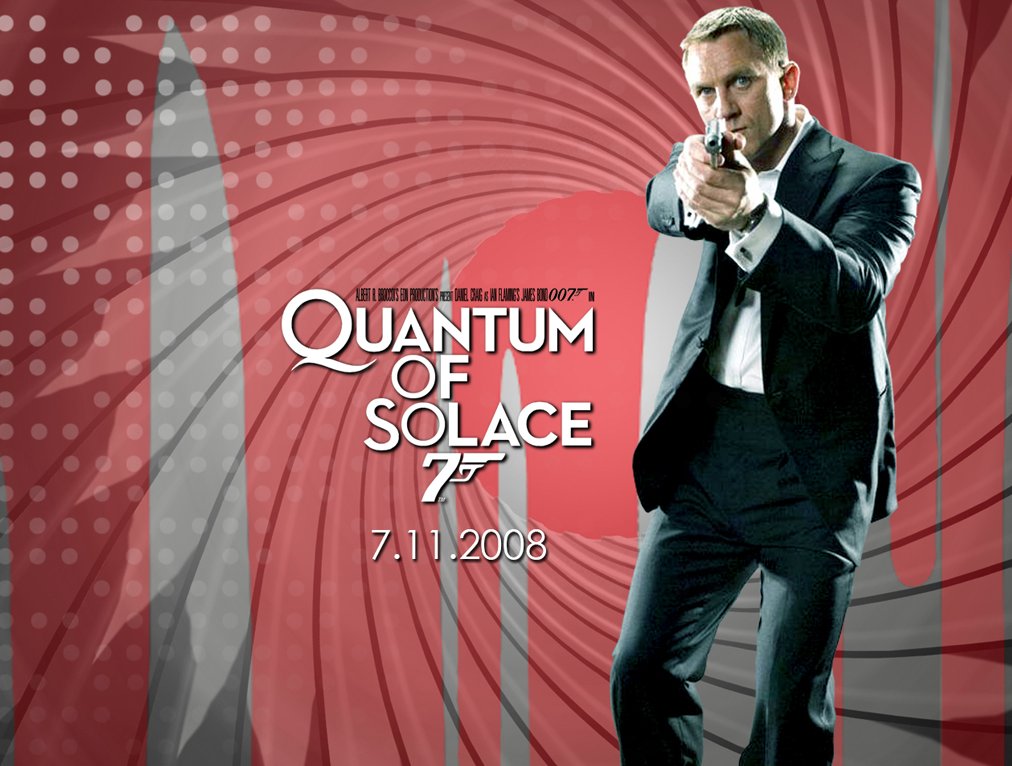

The novels of Ian Fleming have been around for a very long time. James Bond has been given life in so many forms and with so many different actors that is might be fair to suggest that the films (and Fleming’s novels) are among a small number of foundational stories that say a great deal about our culture and values. I will not dwell on this point. Suffice to say, that my viewing of Quantum of Solace, the latest Bond was profoundly influenced by what I have just said. The key metaphor that I want to draw from the film is the balance between fallibility and infallibility that is at the heart of Bond’s attraction as a hero. In an era characterized by the never-ending presence of terrorism, war and violence against innocent civilians, there were two moments in this film that said more to me than the entire film itself. The first came after an endless chase between Bond and a villain which led both men into an open-air arena with thousands of people attending a horse race. The villain fires his gun at Bond and hits a civilian. The film pauses for a backward glance and then returns to the chase.

This raises some important questions. We witness the injured woman falling and so the film feels morally inclined to show the effects of the villain’s violence and ineptitude. But, should Bond not have stopped to help her out? Aren’t heros supposed to be capable of engineering a good outcome to everything that they do? Is the new Bond of the last few films and especially this one really a tragic hero? And, is the death of a civilian merely one part of that tragedy? The answer to these questions can be found in the ways in which justice is defined not only within the film, but within our culture as a whole. In Bond’s world (and among many contemporary movies), the roots of evil are always encapsulated within a broader context of conspiracies driven by megalomania, the desire for absolute power and greed. The overarching goal therefore has to be to destroy the source of evil even if the innocent have to suffer. The villain is more important than the injured woman and what would otherwise be a moral conundrum becomes a passing moment in an endless battle.

The second characteristic of the film that is of interest to me is the way in which Bond escapes all injury during a series of spectacular encounters between himself and the seemingly endless world of evil. Every form of transportation is used to highlight his superhuman abilities and most of his encounters mirror previous challenges in previous films. The film tries to create a sense of potential weakness in his abilities and in the confidence that his boss “M” has in his character. This is all a charade of course, because he would not be Bond if he did not triumph. The ebb and flow between his weaknesses and his strengths opens up a small window for some discussion of the ethics of his violence but this too is no more than a plot vehicle. In the end, Bond triumphs notwithstanding his own lack of a moral framework for his actions.

This is of course the central challenge of the war on terror, itself a metaphorically terrifying and deeply contingent way of solving issues of far greater complexity than the term ‘war’ suggests. So, it was not a surprise to me to recognize that the new Sherlock Holmes film was really a meditation on absolute power, fear of new technologies and on the role of magic and religion in determining people’s actions. Yet again, Sherlock played by Robert Downey seems to evade every form of violence directed his way. He transcends, as in the comic books, every challenge he faces including a series of dockside explosions that throw him all over the place. So, although the war on terror is very much about our general fragility and vulnerability, we have new and recycled heros who are able to withstand whatever is thrown at them. The irony is that the moral centre that is needed to progressively engage with violence has shifted as terrorists have targeted more and more civilians through their most powerful weapon, suicide bombing. Very few contemporary films deal with this issue nor do they explore the issues of inflicting pain on suspects or perpetrators. Torture is present in both films but without much fanfare and even less concern for its implications. The reality is that for better or worse, the moral fibre of contemporary culture is being challenged by events that seem even less rational (if that is possible) than just a few years ago. The challenge is how to bring this theme into the foreground of popular forms of storytelling.