How long will it take before all artists have their own television channels?

Thursday, September 25, 2008 at 12:10PM

Thursday, September 25, 2008 at 12:10PM This question was asked by Stoffel Debuysere. It could be argued that every web page developed and maintained by individuals is in fact operating within a broadcast model. The screen real estate may be different, and the time and place of broadcast may be 24/7, but the reality is that we now live in what could best be described as a world of webs, semantic clouds and visual and aural clusters.

This ecology or imagescape is multi-layered and lends itself to an endlessly proliferating messagesphere that is infinite. I would suggest that self-broadcasting (which is at the heart of the brilliance of Facebook) now determines the ways in which we recognize ourselves in the world. I am not suggesting that the material world which we inhabit and recreate on a daily basis has ceased to exist. Rather, the material world has increasingly developed into mixed messages, which in combination with human action and interaction means that words, for example, can be taken more literally than ever before (the rise of religious fundamentalism) in parallel with an increasingly powerful and rational scientific model (that is at the heart of the engineering behind the Internet). Religion and science now co-exist in an uncomfortable relationship that is strained and for the most part in conflict.

To self-broadcast means to communicate with the unknown, since for the most part readers of web pages and facebook sites are anonymous. You may have 600 friends on Facebook, but you can't know when they are viewing your pages unless they leave you a message. For the most part, broadcasting in this way is asynchronous.

It is of course the same thing with books which exist in an asynchronous relationship with readers.

How long will it take before all artists have their own television channels? Well, they always have been broadcasting whether it was through the gallery system or via picture books or in large museums. The notion of self-broadcasting is as old as most of the systems of communications that we have created over many thousands of years of creative activity within messagespheres and this includes cave paintings.

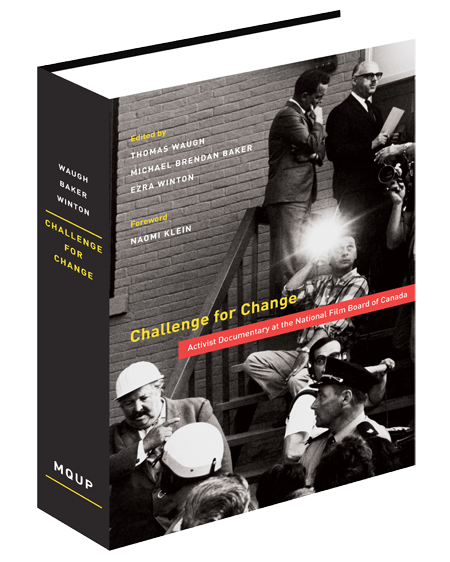

This is a visualization of the entry you have just read.

(Created using wordle)