Entries in Postmodernism (20)

The lost art of reading

Monday, August 10, 2009 at 11:52AM

Monday, August 10, 2009 at 11:52AM The lost art of reading by David L. Ulin of the Los Angeles Times.

The relentless cacophony that is life in the 21st century can make settling in with a book difficult even for lifelong readers and those who are paid to do it.

[Continue reading…](http://www.latimes.com/entertainment/news/arts/la-ca-reading9-2009aug09,0,4905017.story)

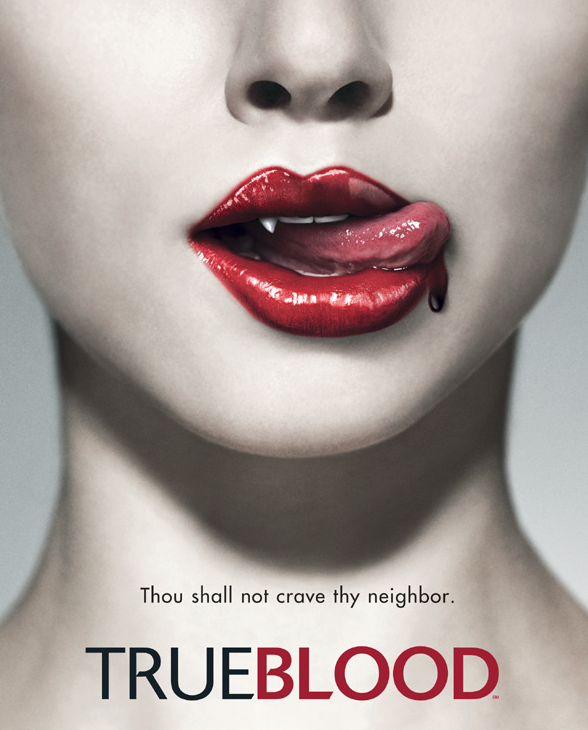

True Blood (2) and the Culture of Vampires

Saturday, August 1, 2009 at 12:18PM

Saturday, August 1, 2009 at 12:18PM

Vampires have become an important part of our current cultural milieu. They exist in various guises and over a number of different media. This is not an accident but a reflection of the zeitgeist that we are living in.

Various commentators have suggested that the reappearance of vampires both as heroes and villains of numerous books and films and television shows suggests an obsession with immortality. Others have referenced Bram Stoker's Dracula which was published in 1897. There are further references to the folkloric origins of the vampire both as metaphor and myth. Combine all of this with further references to the supernatural, the church, demons and monsters and reality seems to be a rather boring and mundane place. And that is precisely the point.

The 'undead' appear in all cultures and there is an obsession with the afterlife in most religions. Vampires don't so much reference immortality as they do history. One of the characters in True Blood, Eric is over a thousand years old. We even see him on the battlefield moments before he is killed by his 'maker' and becomes a vampire. Presumably, since vampires can be anywhere on the earth, they are not only immortal but all knowing. Their knowledge does not let them change their reality. They are stuck inside and outside of history.

However, modern stories of vampires are less transparent, with the vampires actually experiencing some measured conflict not only about their status, but also about their state of mind as well as their emotions. This was brought to the foreground in Buffy the Vampire Slayer with the vampire character of Angel. Somewhat like Bill Compton in True Blood, Angel falls in love with a human and the entire show circles around the existential angst that Buffy and Angel experience as their emotional attachment ebbs and flows. These shows are also connected to the endless procession of TV series which use the supernatural to solve mysteries and murders as in The Mentalist or where the supernatural becomes a source of danger as in Heroes.

The roots of superstition are complex and profoundly intertwined with paganism and spiritualism. One of the most important psychological elements in superstition is projection. Something or someone outside of oneself is responsible not only for our state of mind but for the events in our lives. This sense that control has been lost and that it will be very difficult to regain control is at the heart of nearly all the modern stories that have vampires as their main characters.

Vampires can only reproduce by killing and can only survive on more killing. That sounds a lot like modern definitions of terrorism and is a fair definition of war in general. But, the real underlying fear here is that our society has fallen into a cycle defined as much by anarchy as by societies that no longer clearly know which direction they are headed in and why conventional solutions to differences and crises lead nowhere.

Vampires reflect a deep and embedded nihilism that displaces responsibility for what is happening in the world onto someone else living or dead. After all, from global warming to terrorism to economic collapse, these are not the best of times. Vampires of course cannot see the sun and natural light is their enemy. Darkness, the time of nightmares and dreams and of danger and fairy tales is when they rule.

True Blood which is a critique of vampires and religion and actually links the two is also a brilliant exploration of what happens when magic and sorcery do in fact take over. The results range from endless loss to hope in the midst of decay. In True Blood, the rather medieval charms of shapeshifting are added to the more sinister challenges of witchcraft. In all cases, the universe is out of control and people, normal people if there are any, are always confronting monsters within and without.

The vampires in True Blood actually have a centralized governing structure with a hierarchy and clearly laid out responsibilities. The fact that the male and female vampires can make love to humans even though they are 'dead' suggests quite optimistically that even in a dystopic time sex and love don't die. This is also the central thematic of the Twilight series by Stephanie Myers.

All of this is fundamentally an attack on modernism, on change and on societies which seem to have lost any connections to their roots. There is a deep nostalgia in Bill Compton's face and demeanor. He wants love even though he is dead. He wants to have an impact on a society that discriminates against him. He wants truth where there are only lies. He is charmingly naive and cynical at the same time. He is both young and profoundly aged. He can magically appear from nowhere and move at the speed of light. But, none of this changes the profoundly decayed society that he inhabits. The circle of fear and retribution will only repeat itself. He is history's worst enemy. A great deal is learned only to be lost over and over again. This timeless world of ghosts and screams and fear represents the apotheosis of contemporary angst. Once again as with Six Feet Under, Alan Ball the creator and director of True Blood is a true historian of our times.

Cultures of Vision: Images, Media and the Imaginary

Saturday, June 20, 2009 at 10:39AM

Saturday, June 20, 2009 at 10:39AM Some extracts from my second book. The complete book can be ordered here.

ADORATION: Atom Egoyan's new film

Tuesday, May 12, 2009 at 1:00AM

Tuesday, May 12, 2009 at 1:00AM “Adoration,” the new film by Atom Egoyan is a profound and extended exploration of language and memory through the eyes of a young teenager. In particular, the film tries to understand what happens to a child who cannot comprehend the death of his parents other than through the fragments and ellipses of conversations and comments by relatives and friends.

This is a deeply psychoanalytic film. It is psychoanalytic not because as some critics have suggested it is a coming of age film. Rather, each character has to come to terms with their own role dealing with trauma both within their families and as observers.

The psychoanalyst is the viewer who has to delve into the contradictory narratives that the characters use to justify their state of mind and relations with each other. But, viewers cannot solve the issues, cannot intervene and must struggle on their own with the implications of losing control over the evolution of the story. In some senses, this mirrors the challenges of the main characters. They cannot exert control over their memories or even put those memories into some kind of clear order. It takes an outsider, in this case Sabine a teacher to reestablish some sense of direction for the family.

As R.D. Laing once put it, the problem with families is that everyone has a different point of view of the same experiences, and each person feels that their point of view is the correct one. As a result, families are always in conflict with the memories that they share.

In this case, the child has no memory of his parent’s death other than through the metaphors given to him by his Uncle and his grandfather. The latter blames Simon’s father, Sami for killing his daughter.

What is a child to make of this? The idealizations of memory clash with the realities of a world infected by violence, much of it arbitrary. What if the death of his parents was the result of a terrorist act? Is it preferable to believe that his mother died because of a momentary mistake or because someone perpetrated an act of terror? How does a child interpret the trauma of events like September 11th in the context of personal experiences? How do impersonal events become personal? And what role does the Internet play in opening up the personal struggles of a teenager to the discourses of strangers?

As Simon delves into what turns out to be a true story about a terrorist who sends his pregnant wife on a plane with a bomb designed to destroy it, he learns through the comments of friends and others, that death by whatever means is never romantic. He learns that each person has his or her own history. He discovers the paradoxes of personal discourses, intertwined with myths and illusions and this enables him to make sense of his own history.

It is within this context that Atom Egoyan explores the complex terrain of the conflicts in the Middle East. The death of a couple in a car crash is elevated into a cultural clash. The film tests the boundaries of what can and cannot be said about the conflicts between different ethnic groups bound to ideologies that they often don’t understand. This too is about history and memory. How does hatred develop and why? Simon’s grandfather expresses the classic prejudices of someone who neither understands what he is saying nor the general implications of his words most of which inevitably lead to violence. His violence is discursive. Words matter and more often than not they are used to hurt those whom we do not understand.

Language is this rich space, this fundamental tool of communications that we as a culture have developed and also perverted. It doesn’t matter if it is the Internet or a family supper, what we say and how we say it affects not only how we perceive the world but also how we act within it.

Simon creates a story encouraged by Sabine his teacher that slowly takes on a life of its own. He uses the story to channel his confusion about his parent’s death into a convenient narrative that quite ironically fits into a preconceived cultural pattern in which the accidents of life have to be framed by some sort of rationale. As Simon learns that the value of life lies beyond the trauma of his parent’s death, he decides to purge his grandfather’s influence on him by burning something that was of great value to his grandfather. Simon also burns the Nokia cell phone that he had been using to film a series of interviews with his grandfather before his death. This is one of the most powerful scenes in the film. The cell phone slowly melts, the images on it pixelate, and Simon’s memories are channeled to a new level.

In one of his best books, “We Have Never Been Modern,” Bruno Latour explains that even though time moves forward, history is not so much about the past, as it is about the many ways in which the past and the present always converge. “Adoration” explores this seemingly endless clash between the past, our interpretation of it, and the implications of not putting a personal stamp on the ways in which we interpret our own histories. Truth is the crucial arbiter here. How do we gain access to the truth? Is it through images? Is it through the Internet? Is it through the eyes of a child? Where are the boundaries between innocence and insight?

In the final analysis history can never be reversed. The events of the past such as the death of Simon’s parents cannot be undone. This is the source of endless trauma and unless we can manage it, the trauma takes over not only our daily lives, not only our fantasies but also becomes the very basis upon which we interact with our families and friends.

Much of what we learn in childhood is channeled through the words of our parents and relatives. Many of our memories are the memories of others. The transformation of memory into a discourse we can control is the thematic core of Egoyan’s film. “Adoration” is a masterful story of how this process of transformation and regaining control changes Simon, but it is also an important statement about the bridges that have to be built between childhood and adulthood. Throughout the film there is one constant that unites everyone and it is the violin that his mother played. The acoustics of the violin are like the human voice. In a scene that unites the narrative, (and which we see twice), Simon’s mother stands at the edge of a pier playing a beautiful piece. In the first instance the witness is Simon as a teenager. In the second, it is Simon with his father on the fateful day of his mother’s death. Both instances clash and unite with each other. Time is conflated. All that is left is the plaintiff cry of the violin. Music is always about the evocation of memories.