Hiroshima Mon Amour: The Paradoxes of Postmodernity

Sunday, July 1, 2012 at 4:49PM

Sunday, July 1, 2012 at 4:49PM Some years ago, I was a Professor of Film and Cultural Studies at McGill University. I taught a class I deeply loved with over six hundred students in it. I loved the class because it was so challenging to engage a new generation of students in watching films, many of which they would never have seen, if they had not joined, Intro to Film. When I showed Hiroshima Mon Amour, Alain Resnais’s masterpiece, the screening was disrupted by laughing, not only on one occasion, but many times. I wrote an open letter to the students which is reproduced below.

I want to start with the film which you saw recently, Hiroshima, Mon Amour. During the film, at moments of great intensity within the story and among the characters, when Alain Resnais is exploring to the fullest, not only the question of desire, but the underlying question of the history of desire, many of you chose, for reasons which I can only speculate on, to laugh.

In some senses your laughter bore witness to the fact that we live in a postmodern age, that is, a period of time in which meaning, the ways in which we value and see ourselves and the ways in which we experience our lives on a daily basis, meaning has, in a sense, been lost. Now what does it mean to say that?

The loss of meaning implies that all meanings have somehow become relatively equal, one to the other. When our ethical cores are spread out among competing values and we have few tools to distinguish what is right from what is wrong, meaning disappears.

Just yesterday I was privy to a conversation between some high school students. During this conversation they argued, at a hypothetical level about how much they wanted to kill Salman Rushdie. These were not Islamic students, they were Anglophone and they were white. What disturbed me about what they said was the manner in which they trivialized a very serious moment in our cultural and political history. The Rushdie affair is not only about censorship, not only about different cultures and the way in which they see each other, but it is also about the values which we should, I would say, must, hold dear. What was at stake in what those students were saying was not so much the content of their conversation, but the fact that they could not see the absence of values, which were at the root of their own rather silly speculations, about how they could go about "winning" the Ayatollah's million dollar price on Rushdie's head.

Trivialization. Let me read a very short quote to you from one of the most acute observers of the postmodern scene, even though I consider what Arthur Krokker says here to be overly deterministic, but nevertheless worthy of consideration and thought.

“In this dis-membered world everything appears to be equal. Thus the emotions you might feel from watching an episode of your favourite television show, become interchangeable with what you might feel watching the news, watching for example the actual dismemberment of a person, their corpse. But what are you actually watching? How can you, with anything but the most suppressed of emotions, watch the many dead bodies which parade in front of you everyday on television?”

What is at stake here is the very way in which we see ourselves and if we are simply incapable of registering any feelings anymore, then perhaps Krokker is right. The two people you watched or didn't watch as the case may be in Hiroshima Mon Amour represented both themselves as people and also the historical epochs they were reflecting on. Thus, you will notice that they were both nameless. He represented Hiroshima and she France.

What is the meaning of Hiroshima to you? Have you ever thought about it? What impact did the images of suffering which you saw have on you? Or were you able to dismiss the images as somehow not relevant because it was not your own relatives whom you saw, or because you have decided that the Second World War is something from the distant past, not likely to have affected you and not likely to affect you in the present?

Or perhaps there is such a surfeit of images of pain and suffering on television that you have ceased to worry anymore, after all an image is just that, something you can physically turn off, a piece of plastic, a gathering of pixels. But there was more to the representation of Hiroshima than the man. There was the fundamental question of whether after the disaster and pain which befell those people and their families, and their offspring, the fundamental question of whether desire or love was possible in a world so powerfully haunted by death.

The same question was being posed for the woman. Could she ever love again in the face of the tragedy which she had lived through?

This then is also a question of identification. How do you identify with the present and with history? To what extent can you link your own personal history to the current events we experience on an everyday basis? Perhaps there are no norms left that allow us to judge the distinctions between other people’s suffering and our own lives? Perhaps we have reached the point in our history where suffering is merely a footnote to the present?

In Hiroshima Mon Amour, the main female character talks about her fall from grace, the fact that she loved a German soldier. In the midst of the war, she fell in love with the wrong man. For her, he was not the enemy, which raises serious questions about the nature of enemies, how we define them, and how we explain them to ourselves and to others.

If, in simple terms the enemy is always outside of us, is an—other, then who are we? Are we good? and is the other always bad? She, in the film crossed the line. She fell in love with an individual who for her had transcended the reality of the war, who was not the war, whom she loved with the youthful exuberance of someone just realizing her desires. The film is precisely about this contradiction, about the impossibility of desire ever being outside of history and of the impossibility of falling in love outside of the historical pressures and currents of the day.

It is impossible to love without a history, whether that history be personal or public. If your personal history is at the root of your desires and if that history is always related, intertwined with the history of the time, the period in which you are living, then your desires become or should become, a marker for you of the historical period in which you are living. A moment A marker. A sign.

She loved a German soldier and somehow through that process tried to transcend time and history. But that is not possible. Just as it is not possible for Hiroshima (the man) to possess her somehow outside of time, outside of all of the constraints and difficulties and contradictions of modern-day Japan.

There is more. How could she have fallen in love with a German soldier in the first place? What point of contact was there? The Germans had occupied France and her village, by the Loire. Nevers. So she fell in love with an occupying soldier, an oppressor, whatever qualities he may have had. What allowed her to transcend the conditions of history, the history of a violent occupation, allowed her to love in the midst of such tremendous decay and destruction? The film poses this as a question which cannot be answered. Because the same question arises in the love affair that she has with the Japanese man in the film.

There is a process beyond words, a process which cannot be pictured, a process sometimes which cannot even be imagined, a process governed by innocence and by the pleasures of the body which cannot be reduced to history and the film asks, must we, to retain our humanity, accept that part of ourselves without submitting it to examination, submitting it to explanation?

In her mind love has become associated with pain, with a pain that she must suppress if she is to survive. But pain cannot be suppressed because inevitably it will come out in some form, be that violence, or hatred, or melancholy, or as seems to be the case in the postmodern period a kind of distant nihilism, where the attitude is, who cares, why care, everything is so screwed up anyway, there are no solutions, no way out.

No way out. That feeling, blockage, despair, a deep sense of loss, is the expression of a pain not dissimilar to the one she expresses in the film. For, if we have convinced ourselves that the act of viewing a dead child on the screen or on television is a mere act of fiction, is fiction, then can we also easily convince ourselves that we are to some degree fictions as well. Identity becomes fictional if all of these painful moments no longer resonate with the power they deserve. It takes storytelling to move beyond or outside of history.

This then is the beginning of an argument which we could trace out in relation to this class. For we have watched characters who are both real and fictional, and in so doing, especially with Paris, Texas, we have had to face the fictions which might be at the root of absences which seem to govern the postmodern epoch. Absence.

What if the fundamental organization of meaning at present is dependent on absence? Can you go to Iran? Can you go to the war zones of Afghanistan? Can you inhabit the places and spaces and worlds you desire? Of course you cannot and thus the world you inhabit is filled with absences, which you in turn must fill with your imagination.

Take the following example. If, on a given night you were to be a part of the news that you watch, if you were to enter into the reality being depicted, what would happen? I leave you to speculate on the answer, but think of the woman in Hiroshima coming to grips with her past by entering into that past through the transformation of her Japanese lover into the German soldier. She addresses him as if he were from the past and in some senses he is. So to fill the absence she has to construct him, and by doing that, paradoxically, she comes to grips with the present.

Absences. If we were to immerse ourselves in total absence, in total forgetting, what would we become? The only total absence we have some inkling about is death and even with respect to death we cannot imagine absolute absence.

This is why, in part, she says: "I stayed near his body all that day and then all the next night. The next morning they came to pick him up and they put him in a truck. It was the night Nevers was liberated. The bells of St. Etienne were ringing, ringing.....Little by little he grew cold beneath me. Oh! how long it took him to die! When? I'm not quite sure. I was lying on top of him....yes.....the moment of his death actually escaped me....because even at that very moment, and even afterward, yes, even afterward, I can say that I couldn't feel the slightest difference between this dead body and mine. All I could find between this dead body and mine were obvious similarities, do you understand? he was my first love.........."

They put him (the German solder) in a truck. So, she too dies and is to a degree brought back to life in the place of greatest death, Hiroshima. But she comes to understand her death through a new love and this is both a contradiction and a paradox. Since if death is absolute then how can she be reborn?

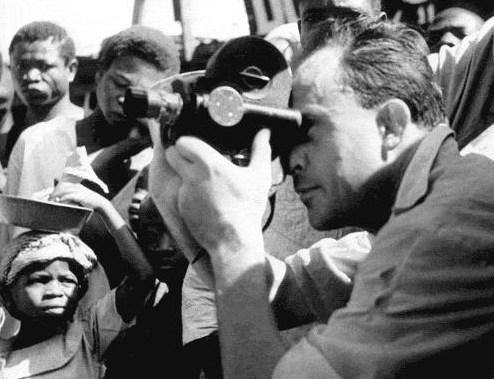

Alain Resnais, one of France’s greatest filmmakers always plays with these paradoxes in his films. He explores the contemporary desire to ‘manufacture’ reality rather than engage with its challenges. Hiroshima Mon Amour is a difficult film, but it did not deserve to be laughed at.