Inference and Reference

Monday, March 19, 2012 at 7:24PM

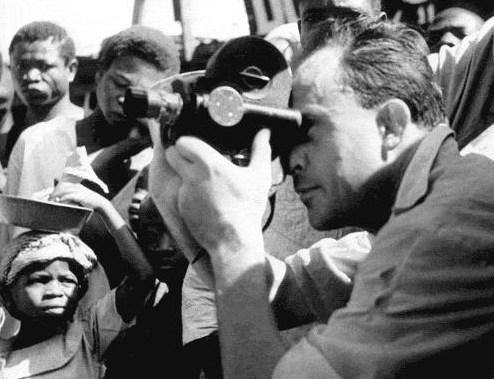

Monday, March 19, 2012 at 7:24PM In 1981 during a public presentation in Paris at La Cinémathèque Française, Jean Rouch said the following:

“I am an ethnographer and a filmmaker. I have discovered that there is no difference between documentary films and fiction films. The cinema, which is already an art of the double, which presents us with a constant movement from reality to the imaginary, could best be characterized as a cultural configuration which balances between various conceptual universes. In all of this the last thing to worry about is whether reality as such has been lost in the process of creation.” [i]

Lest Rouch be misinterpreted by purists of the documentary genre he went on to say that as a filmmaker he creates the realities he films. He sees himself as a ‘metteur en scène’ as well as someone who has to improvise everything from camera angle to camera movement during the shooting of a film. This process is inspired by the kind of personal choices which inevitably rely upon the imagination of the filmmaker. The key to Rouch's approach here is the role which he sees artifice playing in the construction of any image or as he put it, the way the filmmaking process irrespective of genre is ultimately a sharing of dreams at the level of production and performance. Rouch's statement can be seen as a counterpoint to efforts on the part of documentary filmmakers to overinvest in the realist enterprise. It could also point the way to an examination of why images which “look” real have such a seductive appeal. Most importantly what Rouch suggested is that the image doesn't play as important a role in the production of meaning as filmmakers would like to believe. In much the same manner as Chris Marker in “Sans Soleil,” Rouch's statement questions the place of referentiality within the documentary form and to some degree looks outside of the image for an understanding not only of the message but of its relationship to performance and projection.

[i]From documents presented at the celebrations for the 50ieth anniversary of the National Film Board in June of 1989.